Little

Wonders |

|

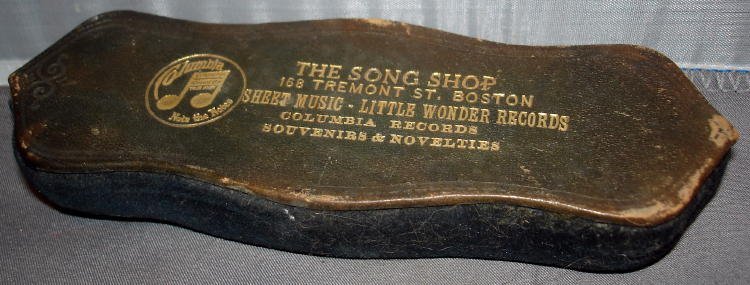

| In 1914 the recording industry was a near monopoly controlled by Columbia, Edison and Victor. -These companies owned all of the most important record-manufacturing patents, and used this market power to keep the prices of records quite high – $.75 to $1.00 each (close to $20.00 in today's money). -This price put recorded music out of the reach of most people. Enter Little Wonder records, brought to market by Henry Waterson (see photo and announcements to the trade in Talking Machine World, October 1914, p. 35 and The Music Trade Review, October 17, 1914, p. 53 at left). -Henry Waterson was the business partner of Irving Berlin, serving as president of the music publishing company, Waterson, Berlin & Snyder (see photo of these men at left). -These lateral-grooved, acoustic records made some compromises in quality – measuring 5½ inches with tight grooves on a single side (compared to the more standard 7- and 10-inch double-sided discs), playing for a minute to two minutes (compared to the more standard two to three minutes per side; click here to hear the difference between the shortened and regular version and follow along with the sheet music), and not sold in sleeves – but were priced at only 10 cents in most of the country (even though the announcements say these were going to be priced at 15 cents; see ads at left showing the higher prices of 15 cents in Oakland, CA and 25 cents in Fairbanks, AK undoubtedly because of the higher shipping prices to get the records out there). -That price point, together with the popularity of the tunes that were recorded, made Little Wonders an immediate and extraordinary success. Millions and millions of these records were sold in the nine years the label was alive, more than 20 million from August 1914 through June 1916 alone.- In fact, so many records were being sold that Columbia initially couldn't manufacture the records fast enough:- In January 1916 Waterson paid Columbia $12,305.10 to install forty more record presses to meet the demand for these records.- While it has not yet been possible to confirm that the proposed building was built, blueprints for a new Columbia factory building (labelled "Building No. 77", see left) in Bridgeport, CT show a sizeable commitment to Little Wonder.- Plans for the second floor show considerable space allotted to storing Little Wonder records, while the fourth floor makes specific mention of 80 presses for Little Wonders along with dedicated finishing benches, conveyors and chutes to record storage. The records were sold through 5- and 10-cent stores like S. H. Kress, S. S. Kresge, F. W. Woolworth, United 5 & 10 Cent Stores, and J. G. McCrory (see postcard views of these stores at left along with the label on the back of my record #64 and an article that describes how to build a window display like that seen at McCrory, and shipping boxes used to send sample records to McCrory), along with other stores such as the Home Amusement Company.- The records were also sold through mail-order catalogs such as The Charles William Stores (see postcard at left) and Montgomery Ward, and especially Sears, Roebuck and Co. (click here to see the listings in these catalogs).- In fact, the 1915 Spring/Summer Sears catalog (the first catalog to feature these records; see scan at left) mentioned that "eighteen thousand Little Wonder Records were sold by one store in Boston the first week they were offered for sale." -Sears was probably attracted to these records because they fit Sears' strategy of offering merchandise at very competitive prices.- And the records were sold through wholesalers like Plaza Music Company and Selchow & Richter (see their ads to the trade at left). There is evidence that these records were also sold in Europe -- at least in England and Italy -- and in Asia -- at least in Shanghai. -My copy of Little Wonder #99 contains a tax stamp from The Copyright Protection Society (Mechanical Rights) Ltd., a British organization (see photo at left). -And there is an Italian catalogue of Little Wonder records ("Piccola Meraviglia" - "Little Wonder" in Italian; click here to page through the catalogue). -Although the catalogue is not dated, it features the "child conductor" Little Wonder label on the cover, which would date it from 1919 onward. -The catalogue contains a 200-series of operatic records that seems to have been produced and sold only in Italy (some of which have been found) along with a few records from the American series. -And see the ad at left that seems to have appeared on the front page of the January 18, 1919 issue of The North-China Herald, describing Little Wonders as "the marvel of the age [and] a splendid gift for kiddies." The sale of the records doesn't seem to have been supported by an extensive advertising campaign -- and the sales figures certainly indicate that one was not needed. -Most of the advertising that has been found was aimed at the trade (see the Advertisements page), although the court papers (discussed below) say an advertisement was placed in The Saturday Evening Post and that monthly flyers were created (these have not yet been found -- if you have the ad or flyers, please contact me). -Waterson did use, at least occasionally, his sheet music business to tout the records by listing the Little Wonder record number inside the sheet for the tune (see the Sheet Music page for some examples) -- an early instance of cross-promotion. The success of the records prompted Waterson to think of other related businesses, some of which were launched.- In February, 1915, riding the success of the records, Waterson brought out a line of piano rolls (see announcement in Variety, February 20, 1915, p. 5 and the ad in 5 and 10¢ Store Magazine, July 1915 at left).- Waterson, Berlin & Snyder were going to open a store themselves to sell these records and a ten-dollar phonograph (Talking Machine World, February 1915, p. 25; the phonograph was also mentioned in the October 1914 announcement), but changed their mind because they couldn't keep up with demand (Talking Machine World, March 1915, p. 43). -There is some debate about whether the phonograph referred to is the one shown at left, manufactured by the Boston Talking Machine Co. and called the "Little Wonder," but that's unlikely because this phonograph, at least initially, was designed to play only vertical records. -It is also possible the phonograph was a model called, "The Baby," which was advertised in late 1915 and was one of the first to mention Little Wonder records specifically (see the teaser and follow-up ad in Talking Machine World, November and December 1915, at left), but the data on this point are sketchy. Other inventors and businesses were also trying to capitalize on the success of Little Wonder records (including Columbia, which is noteworthy as will be shown below).- The patent shown at left -- assigned to Columbia -- was for a tone arm specially suited for small talking machines designed for little records.- Also at left is a photograph of the Geer Record Repeater, specifically designed to allow a Little Wonder record to play over and over again without the need to manually restart the needle at the beginning.- In addition, countless phonograph companies began to advertise the ability of their machines to play Little Wonder records, while other businesses advertised they were carrying Little Wonders (see the advertisement at left for a Cecilian phonograph and the record duster, for example). The success of these records revolutionized the recorded music industry by driving down the price of standard records. -Recorded music had suddenly become accessible to almost everyone. -Dealers were getting concerned (see Talking Machine World, February 1915, p. 48 and June 1915, p. 49 at left) and Victor felt the need to publicly deny its involvement in their creation, while criticizing the endeavor (see Talking Machine World, March 1915 p. 54). -Manufacturers attempted to respond, but as reported in The Music Trade Review (November 27, 1915, p. 76, at left), manufacturers' efforts to produce a competitive record ultimately died, probably because "...a certain prominent publisher [failed] to enter into the plan." -That publisher could well have been Waterson who would have had no interest in joining and aiding others to compete with himself. -These concerns persisted at least through 1917 (see The Tuneful Yankee, June 1917, p. 8, at left for example). There has not been universal agreement about the origins of Little Wonder records, but I have unearthed court documents generated by lawsuits between the founders (including trial papers and an appellate decision) that reveal what is probably the definitive version of events (reading the court documents requires Adobe Acrobat Reader®; click here for free download). - The two key people were Waterson and Victor H. Emerson (see photo at left). -Emerson was the superintendent of the record-making department of the Columbia Phonograph Company, where he was responsible for master record reporting, making arrangements with recording talent, making the master or wax records, and, as a sideline, perfecting inventions related to making master records. According to the court documents, in July 1914, Emerson told Waterson that the American Graphophone Company, of which the Columbia Phonograph Company was a subsidiary, was about to manufacture a small record, of about five and one-half inches in diameter (Emerson may even have invented them). -The plan was to sell the records to the public for ten cents. -Emerson introduced Waterson to George Lyle (see photo at left), the vice president and general manager of the Columbia Phonograph Company, and Waterson became interested in being the exclusive sales agent for the records. -Waterson was a good choice because of his music publishing business and his network of other publishers – these would be needed to get access to titles the public wanted to hear at royalty prices that would allow the records to be sold at a profit (more about that below).- And Emerson brought connections to the singers and musicians whose talents would be needed for the recordings. A contract was signed in August, 1914 that gave Waterson exclusive sales rights for five years. -Under the terms of the deal, Waterson agreed to take American Graphophone's output of small records up to a quantity of 500,000 per week, and Waterson was to pay all copyright/royalty costs. -Waterson agreed to pay six cents per record when the recorded material was copyrighted, and six and one-third cents when it was not. -Waterson sold the records at seven cents (see one of the ads to the trade), and therefore the profit would either be one cent or two-thirds of a cent on each record sold, excluding the royalty payments. Interestingly, one of the other terms of the contract required that both parties keep Columbia's role in manufacturing the records a secret, which explains why this was never publicly admitted at the time. -In fact, even by 1918 when the records were back in the hands of Columbia, Columbia's listing in the trade directory contained in the March issue of Talking Machine World only mentioned that they manufactured ten- and twelve-inch "Columbia" records. Waterson applied for the trademark on December 5, 1914 (see left) and the records were manufactured at Columbia's plant in Bridgeport (see postcard at left) using Columbia's patents. -The dates on the back of the records refer to patents owned by Columbia; by 1920 an additional line was added to the back to say "Made in United States of America" (both versions are shown at left). -Emerson supplied at least some of the talent that made the original records. -In fact, Emerson arranged for Henry Burr to record "Ben Bolt" as a pilot recording to test whether these records could be manufactured, and this recording became Little Wonder record #1. -Some of the original musicians performed as a favor to Emerson and to stay in good stead with Columbia, but – and there is some confusion on this point – at least some were paid. -For example, Albert Campbell, Arthur Collins and John Meyer received $25 each for recording #56, #64, and #65; Arthur Collins received $15 for recording #17; and Byron Harlan and Arthur Collins received $60 each for recording four duets (numbers unknown). -These are the arrangements that made Little Wonders possible. Clauses in the contract required Columbia "to designate by some suitable process, on each and every record...the name of the musical composition or selection contained upon the record," but if Waterson wanted a label affixed he would need to pay the costs associated with printing and shipping the labels to Columbia. -This might explain why the earliest records had no paper labels, and why paper labels appeared about the time Columbia took the records back (see below). Competition for these records arrived from Emerson himself in 1915. -Emerson left Columbia in 1914 or 1915 and started his own recording company, Emerson Phonograph Company, Inc. -Emerson had just purchased a patent from George T. Smallwood (patent number 639,452) that allowed him to manufacture a lateral-groove record with a 45-degree groove wall. -Emerson's line included 5 7/8 inch discs, obviously directly patterned on Little Wonders, and these were produced through 1919. In addition to competing with Waterson, in 1915 Emerson sued him. -Emerson claimed there had been a verbal agreement between them whereby Emerson was to have received one-half cent as a royalty for each record sold, and that he had not been paid in full (see the "Emerson v. Waterson" section below for details on the trial). Around 1916, while the lawsuit was working its way through the courts, control of the Little Wonder label was transferred to Columbia, which then operated Little Wonder as a separate division. -(There was a clause in the contract that allowed Columbia to default on the contract and take the distribution of the records back for a payment of $10,000 to Waterson, but it is not clear whether that was the way in which the records returned to Columbia.) -The last label style contains an address for the Little Wonder Record Company as 2036 Woolworth Building, New York, NY, which is where Columbia's offices were located (see postcard of the building at left along with articles about the succession of managers of the Little Wonder department, one of which mentions the location: Talking Machine World, December 1919, p. 35) and the trademark for that label style was held by Columbia (see trademark at left). Little Wonder records were still attracting attention in 1917 (see listings at left from the February, June and July issues of The Tuneful Yankee, a hobbyist magazine) and Columbia was still supporting the label with retail advertising, at least occasionally (see ad from the February issue of The Tuneful Yankee).- And at some point, although the date is unknown, Columbia created a mailer (see left) that people could use to mail Little Wonder records, presumably an attempt to stimulate sales of the records as gifts.- By 1918, however, sales were beginning to decline as competition increased and the public's interest in small discs decreased. -The patent monopoly was ending as the patents expired or were invalidated, and independent recording companies were starting. -The major labels were reducing their prices for standard-sized records, which were of better quality. -In 1919, Little Wonders were being offered as rewards to readers of some magazines in exchange for signing up new subscribers (see listing of Youth's Companion subscriber premiums), and at least one company was offering the records for as little as $6.00 for 100 (see ad in Popular Mechanics at left). -Some time around 1920, one record store owner seems to have been giving away Little Wonder records to promote his business (see the promotion record at left). -The 1921 Fall/Winter Sears catalog was the last Sears catalog that contained Little Wonder records. -This decline means that, unlike most antiques, the latest Little Wonders, which are more rare, are more valuable. At some point, though, Columbia entered into a partnership with Rust Craft, one of the earliest and very successful producers of greeting cards and other items (something like Hallmark of today).- That partnership produced a series of children's records, titled "Mother Goose Records," which were attributed to the Little Wonder Record Company.- These records were sold in a decorated box (see photos at left) and were produced by applying a different label to Little Wonder records (see photo at left, where the matrix number of the original LW record is visible).- In this way, LW #943 became 464-B and LW #814 became 464-C.- I do not know which record was used for 464-A (assuming there was one), or whether the series continued. -If you have any additional information about this series, please contact me. By 1923 no new Little Wonder records were being recorded, undoubtedly related to Columbia's bankruptcy that year.- Waterson died on August 10, 1933 (see obituaries at left; the last line of the Herald Tribune obituary ends "...won several big stake races.") having prospered in many other businesses in the years following his Little Wonder venture. Emerson v. Waterson The table at left shows the chronology of events in the circuitous path of the two trials and two appeals of this case, and the table below shows the two sides of the arguments that were made.- The first trial was dismissed after the cases were presented. -Emerson "clarified" the terms of his contract with Waterson after the first trial, now claiming that the contract required Waterson to pay no more than a half-cent per record as a royalty payment. -This cap would have resulted in a profit; Waterson had paid more than the cap (see the table at left for my reconstruction of the detailed accounting Waterson provided during his deposition) and claimed there was none. -The accounting shows that royalties accounted for 86% of the expenses, and nearly 80% of these royalties were paid to companies controlled by Waterson, Berlin & Snyder. -So while it appears that Waterson lost money in the Little Wonder Company, he seems to have more than made up for these losses in the money paid to his publishing businesses. Also note that the accounting was reported for two time periods: the first from August 1914 through April 21, 1915 and the second from April 22, 1915 through June 30, 1916. - This is because Emerson assigned any interest he might have in Little Wonder records to the Emerson Phonograph Company on April 21, 1915. -If Emerson was successful with this lawsuit, he would have benefited personally from profits before April 22, 1915 while the Emerson Phonograph Company would benefit from those after. One other interesting point is that Waterson's testimony indicated he had promised profit percentages to other music publishers, apparently as a way to gain access to their tunes.- In addition to the royalty payments due, Jerome H. Remick was to receive 10% of the profits and Shapiro, Bernstein was to receive 5%.- There were no profits, however, and so these publishers would not have received any payments except for the royalties. The New York Supreme Court, on October 11, 1917, agreed with Emerson (see the appellate decision and Talking Machine World, October 1917, p. 126 at left). -That verdict was overturned, however, by the Appellate Division on May 31, 1918 on the grounds that there was insufficient proof that such an agreement existed.- The court went on to state that since the existence of a contract was not established, there was no need for it to consider whether Emerson could personally profit from a deal he made as an employee of the company (see the appellate decision and note that Talking Machine World got this wrong: see June 1918, p. 32 at left). -Emerson appealed the reversal, but was not successful (decision rendered on March 19, 1920). EMERSON AND WATERSON VERSIONS OF EVENTS

Sources:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||