Bubble

Books |

|

|

|

Little Wonder records were related to another major market innovation -- books and records for children. -In 1917, after Columbia had taken Little Wonder back from Henry Waterson, Columbia formed a partnership with Harper & Brothers to produce a series of fourteen children's books -- the "Bubble Books." -(See the Bubble Book discography for pictures of all of the books mentioned in this section.) -These were the earliest series of books and records published together especially for children, and were known as the "Harper Columbia Book that Sings" (the name that also appears on the records).- Ralph Mayhew (see photo at left), one of the authors, patented the books on August 7, 1917 (see patent at left), and Harper & Brothers held the copyright (also dated 1917).- The other author was Burges Johnson, and the beautiful, full-color line drawings were by Rhoda Chase.- The singer on all of the records is most likely Henry Burr. Ralph Mayhew was interviewed for an issue of Printers' Ink in 1921 (click here to read the interview in full -- requires Adobe Acrobat Reader®; click here for free download).- He relates the story of coming up with the idea while thinking of ways to popularize Mark Twain's writings.- He brought the idea to Harper & Brothers, his employer, who was interested and then began his two-year travail finding a record company to produce the records.- After many, many turn downs -- record companies simply didn't believe there could be a market for these -- he was finally introduced to the senior executives at Columbia and made the deal just in time, barely, for Christmas 1917. Just like Little Wonders, millions and millions of these books were sold (1.5 million from January through May 1920 alone, according to one ad, with 3 million expected to be sold in all of 1920, according to another ad or 3.5 million according to yet another). The books were initially sold in book stores, music stores, and phonograph stores, with toy stores added in 1920 (see ad).- Sales were helped by early reviews, which were quite favorable (see, for example, the review in the November 15, 1918 issue of The Bookseller, Newsdealer and Stationer and, not surprisingly, in Harper's own Harper's Magazine in January 1920, both at left).- By March 1920, the sales were so large that Harper & Brothers took on seven new floors of office space, with one entire floor reserved just for shipping (see New York Times Book Review article at left).- The photograph at left, probably taken in East Texas, shows one of the happy customers at the time and the photograph below it is taken from Columbia's Grafonola in the Class Room (1919 and 1920), which also advertised the availability of Bubble Books in its pages.- The success of the first book led Harper and Columbia to believe there might be a market for the second, and so the series was born. The books tell the stories of a lonely boy who was given a magical pipe by his fairy godmother.- The pipe blows bubbles with Mother Goose characters inside that come to play with him and sing songs.- Bound into each book are sleeves that hold three, single-sided, 5½" records.- Children could play the records and sing along with the tune as they read the stories.- The books themselves measure 7¼" x 6".- And, as the discography reveals, the catalog numbers of the Bubble Book records are numerically part of the Little Wonder series.- The most prevalent labeling style for the Bubble Book records (blue printing on a cream background) is the same color scheme most prevalent on Little Wonder records at the time the book series began (see the Record Label section). The Harper & Brothers versions of the Bubble Books were produced from 1917 until 1923, in at least three editions.- There was a "first" edition made in 1917 of at least Bubble Book #1 that has no volume number on the spine and no list on the reverse of the title page of other books in the series, although all copies I've seen end with the words "End of Book No. 1."- (If you have a copy of Bubble Book #1 that does not end with these words, please contact me.) - There was a "second" edition made of #1-9 when it was apparently still not clear how many of these books would be produced.- This second edition was published in 1918-1919. -(These dates, and the other publishing dates for the Harper Columbia Bubble Books provided below were identified using the publishing codes on the copyright page; see Note below.)- This edition does not have the volume number on the spine, and has only the first several of the books in the series on one of the first few pages.- For example, this second edition of Bubble Books #1 and #2 and Bubble Books #6-9 show the listing for the series that only goes up to Bubble Book #9 (as shown at left), while Bubble Books #4 and #5 in this version have advertisements for the series that only include volume numbers up to that book (as shown at left). The "third" edition of Bubble Books #1-9, published in 1920, does have the volume number on the spine and contains listings for all twelve books.- The photo at left shows the spine of the second and third editions of Bubble Book #4, along with a version that has a color variation.- (Curiously, though, the series listing in this red-colored third edition of Bubble Book #4 only went up to Bubble Book #9, like that contained in the second edition of Bubble Books #6-9.- I have found no other Bubble Books from the third edition that did not include the full series, and have no explanation for this one.)- All Bubble Books #10-12 date to 1920 (see review of Bubble Book #12 at left) -- the same year the third edition began, which might explain why there are no second-edition versions of these later books. -These books contain listings for all twelve books (as shown at left), and all have volume numbers on the spine. There were also variations in the color of the labels that might be associated with the editions -- see the Record Label section for a discussion and pictures. Interestingly, the series listings in Bubble Books #13 and #14, published in 1922, contain a reference to Bubble Book #15, "The Robin and the Wren," which was never published in the acoustic series as far as I know (see picture at left).- Its debut was delayed until 1930 when it was published in an electric version (see discussion below). The price of the books rose and fell over their lifetime (see the Advertisement section).- The books were initially priced at $1.00 each, and increased to $1.50 in 1920.- That price increase didn't hold, however, and by 1921 the books were priced at $1.25.- Even that price couldn't stick, and by 1922 the books were being sold at their original price of $1.00 each.- According to one of the ads, these price reductions were caused by anticipated reductions in manufacturing costs (labor, material, and distribution).- Rather than keep the additional profit these declining costs would create, Columbia reduced the price, most likely as a way to stimulate demand that had fallen off as the price increased. One of the most rare collectibles associated with the Bubble Books might be the Cut-Out Bubble Book (see cover at left), which was published in 1922 and sold for 60¢.- The book was advertised in some copies of Bubble Books #13 and #14 and in the June 1922 issue of Harper's Magazine, which also announced the publication of those two new Bubble Books (click here to see the ads and page through the book and its patent).- This book contains figures from the first three Bubble Books that could be cut out, assembled, and placed on top of the record to dance along with the tune as the record played. The Bubble Books were not just available in the U.S.- At first, the U.S. versions were simply sold abroad, at least in England, and priced at 7s 6d (see review in The Sound Box at left).- Columbia later made a deal with Hodder and Stoughton, Limited in London for a British edition sometime in late 1920 or early 1921.- Hodder and Stoughton, founded in 1868, was -- and continues to be -- a UK publisher of general fiction, religious, and children's books.- Columbia still provided the records (which were pressed in the U.S. and were identical to the U.S. version), but Hodder printed the books in Great Britain.- This series was known as the "Hodder-Columbia Books that Sing," - As far as I know, Hodder only published books #1-10, despite advertising the availability of #11 and #12 in the listing at the front of each book. The Hodder versions are, most likely, British printings of the U.S. books, as evidenced by identical spellings of words such as "favorite" and "savor" in both the Hodder and Harper versions.- Other evidence for this theory is provided by Bubble Book #8.- All other Bubble Books in the series are identified in the U.S. edition as "Harper Columbia" in large print on the cover, and this type is changed to "Hodder-Columbia" on the UK editions.- Bubble Book #8, though, is identified in tiny print in the border at the bottom.- This very small print says "Harper Columbia" on the Hodder version as well (see detail at left).- Perhaps the printers did not see this identification when they were preparing the plates for the Hodder edition. There was a substantial, multi-faceted marketing campaign driving sales of the Bubble Books -- targeting retailers to build demand and retail customers to build sales.- While some advertising appears in 1918 and 1919, in 1920 an extensive advertising campaign targeting retail customers was launched (see the Advertisment section) -- at a cost of $75,000 (close to $1 million in today's dollars) according to trade ads in the August 21, 1920 and October 2, 1920 issues of Dry Goods Economist and the September, 1920 issue of Talking Machine World.- According to a November, 1920 ad in another trade magazine, The Bookseller, Newsdealer and Stationer, this was "the largest campaign ever devoted to books," a claim repeated in the review of Bubble Book #12 referred to above and published in the same issue (see left).- The same ad describes and shows several stands, displays, brochures, and advertisements store owners could use to build demand, and these were touted in ads in other trade magazines (Talking Machine World and Dry Goods Economist). - This support material also included print blocks (two shown at left) that dealers could use to place newspaper advertisements.- At some point, a stamp was printed (see left), but how this was distributed and used is not known.- Jacob Smith, writing in the Journal of Children and Media in 2010, argues that Bubble Books entered the market just at the time women’s role in the household was changing and their performance as mothers was being judged in new ways.- Mothers were increasingly busy and time-pressured, and were looking for new ways to both educate their children and keep them amused.- The advertising campaign for Bubble Books incorporated these messages, targeting children, mothers and retailers.- At the same time, the campaign was educating retailers that children were an important – and continuing – source of business. Retail advertisements were placed in newspapers, women's and children's magazines (such as The Ladies' Home Journal, Woman's Home Companion, St. Nicholas Magazine, John Martin's Book, etc.) along with general interest magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post and the Quality Group (World's Work, Scribner's, The Century, The American Review of Reviews, The Atlantic Monthly, and Harper's Magazine), a group of magazines targeting the most affluent (see ad in The Atlantic Monthly at left).- Ads appeared in almost every issue of Harper's Magazine from December, 1917 through December, 1922, not surprising, since it was also published by Harper & Brothers.- Youth's Companion was also part of the marketing campaign -- this magazine used Bubble Books as a premium that subscribers could earn as a reward for signing up other people as subscribers (see page at left).- The books were also included in the mail-order catalogs of Montgomery Ward from 1919 through 1922. -(There is an interesting error in the Montgomery Ward catalogs of 1919 -- catalogs #91 and #92.- Those catalogs include a Bubble Book #9 titled "Topsy Turvy" that was to have included tunes called, "Owl and the Pussy Cat," "The Fox and the Goose" and "The Fly and the Bumble Bee."- Book #9 actually became "The Merry Midget," which had similar, but different songs.) There were many other components of the marketing campaign in addition to advertising by Harper directly.- In the U.S., for example, sales of Bubble Books were being stimulated by child actors from New York hired to participate in organized Bubble Book parties around the country (see just three examples of these newspaper advertisements for the parties at left).- These parties were apparently the inspiration of children in Patterson, New Jersey who asked their parents to make them costumes of the characters.- Harper & Brothers learned of their idea and created a play in which the children take the part of the characters from the books (see this December 25, 1920 ad in Dry Goods Economist), which they put on in various types of venues throughout the country (including "one of the biggest theatres in New York City").- According to Frank Andrews, writing in the Winter 2001 issue of Hillandale News, one party in Omaha, Nebraska was reported to have attracted over 1,000 children.- And in London, Hodder and Stoughton organized a window-dressing competition for dealers in the fall of 1921.- (See also the record sleeve at left from an English record and phonograph dealer advertising their Bubble Book specialty.)- Harper & Brothers attended trade shows to spark interest in the books among attendees: The Toy Fair in New York City from February 7 through March 12, 1921 (featuring a Bubble Book Party every afternoon in the Bubble Book Theatre at Bush Terminal Sales Building, 130 W. 42nd Street, the location of the Bubble Books sales organization; see ad) and an August, 1922 national merchandise fair attended by hundreds of wholesalers, covered in the trade press (see article in The Music Trade Review, August 19, 1922 at left).- At the end of 1922 or in 1923, the Bubble Book sales offices moved to Franklin Square, and Harper launched a direct mail campaign, citing at least two million books sold (see letter at left). In 1923, trade ads in Talking Machine World were suggesting that dealers hold a "Bubble Book Hour" in their store to drive traffic and sales in their store during off hours, and also mentioned that the songs and stories were being broadcast on the radio.- And at least one ad (Child Life, December 1923) tells parents to ask about Bubble Book Hours in any good phonograph, department, or book store.- Huge numbers of ads for Bubble Books began to appear in newspapers around the country and abroad, some from stores letting people know they had the books for sale (see, for example, the ad from the Manchester Guardian at left), or were having a "Bubble Book Party" as described above.- Other media mentions included the daily newspaper program listings from the high-powered radio station WJZ in Newark, New Jersey.- This station ran weekly broadcasts (generally 30-minutes on Sundays at 6:30pm) featuring readings and recordings from the Bubble Books, which could be picked up throughout the country because of the power of its signal.- I have found listings for these broadcasts from April 2, 1922 through July 13, 1924 (see the last radio program listing that I know about at left), which is well into the Victor era described below.- I also have correspondence written by children to Ralph Mayhew in care of WJZ that dates the radio show as late as April 1925. The success of Bubble Books also stimulated sales of phonographs and other records.- Bubble Books led some types of stores that had never carried either books or phonographs before to bring in both -- expanding people's access to recorded music.- It was also reported that people who had no interest in purchasing phonographs for themselves needed one to play the Bubble Book records for their children -- and some then became enamoured with recorded sound and purchased other records for themselves.- And in some cases, people with expensive phonographs didn't want their children playing with them, and so they bought a cheaper model for the children to use themselves.- At least two companies developed phonographs explicitly tied to Bubble Books, Victor (the Victor Victrola 1-2 pictured at left and described below), and the Plaza Music Company (The Kiddiepact, which was manufactured in many colors with different decals from the Bubble Book series, also pictured at left).

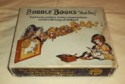

By September 1924 the copyright and patents had been acquired by the Victor Talking Machine Company (see The Music Trade Review report on the acquisition and a postcard showing the factory at left), which was quite pleased to tell its dealers that this meant there would be no competition from the Harper Columbia version (see article from Voice of the Victor, September 1924, at left).- In fact, it appears the remaining stock of Harper Bubble Books were being sold off for 25¢ during at least one massive sale, according to a Gimbel Brothers ad that appeared in the New York Times on September 11, 1924 (see left).- Victor then produced a series of six Bubble Books, each of which contained two of the original Bubble Books and were sold for $2.00 (see description at left on glassine paper; original use of this paper is unknown).- These books were oversized in comparison to the Harper Columbia series, measuring 9½" x 7¾".- The three bound-in sleeves each contained double-sided records (rather than the single-sided records of the Harper Columbia series), and these records were also oversized in comparison, measuring 7" (rather than the 5½" of the original).- Ralph Mayhew had just received a patent for another method of mounting records into books (see patent at left), but that method was not used by Victor.- Sales of the books, at least initially, must have exceeded Victor's expectations since they speeded up production of the fifth and sixth books to have them available in time for holiday sales (see article in The Music Trade Review at left).- (The eighth and ninth original Bubble Books were not included in the Victor series, but the reason for this omission is unknown.) The records in this version were also recorded acoustically, just like the Harper Columbia series.- (There is some confusion on this point, but see the footnote in the 1927 Victor Records catalog listing at left for the definitive answer.)- Victor worked hard to promote their books, including giving tips to dealers about how to decorate their windows (see articles from Voice of the Victor, November 1924 and July 1925, at left).- But just like the Harper Columbia series, the price declined over time, to $1.00 in 1927. While Victor controlled the copyright, it produced a phonograph decorated with images from the Bubble Books and priced at $18.00 -- the Victor Victrola 1-2 (see photograph at left) -- but surprisingly, did not mention the tie-in between the two in their announcement of the phonograph to dealers. By 1930 Columbia was again manufacturing Bubble Books.- Columbia issued a new boxed set of four Bubble Books (see outer box at left), sized like the originals, this time in partnership with Dodd, Mead and Company (see announcements in the New York Times at left).- And now Ralph Mayhew held the copyright.- The records in these books were recorded electrically instead of acoustically, and instead of appearing on three single-sided records, the three tunes were manufactured on one double-side record and one single-sided record.- Two of these books reprised the last two books of the original acoustic series (#13 and #14), and two books were new, including the long-planned "Robin and Wren." As Columbia was winding down its production of the Bubble Books, it released some of the electrically recorded records from Bubble Books #13 - #16 on its Clarion label (sometime between 1930 and 1932).- These were not in the books, but came in specially designed sleeves (see the record and sleeve at left).- Some labels credit "Jack Hill" as the performer while other credit "Tom Lee," both pseudonyms for Henry Burr. The historical importance of these books has been recognized by the Library of Congress as part of its National Recording Registry.- Each year, 50 recordings are selected for the Registry because of their cultural, historical, or aesthetic significance.- In 2004, the second year of the Registry, Bubble Book #1 was included because of its importance as the first children's book-and-record series. Sources:

Note:- Here is the key to dating a Harper & Brothers book using the "letter dash letter" code found on the copyright page of the book. -The first letter of the series is the month: A=January, B=February and so on, except the list skips "J" so K=October, etc. - After the dash is the year: M=1912, N=1913, and so on, except again there is no "J". -When you get to Z (1925), the alphabet starts over with A=1926 continuing through Z=1950 (again, skipping "J"). |

||||||||||||||||||||